Int. J. Life. Sci. Scienti. Res., 4(2): 1707-1712,

March 2018

Tuberculosis Among Household

Contacts of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Cases at a Tertiary Hospital

in Lucknow, India

Rajeev Kumar1*,

RAS Kushwaha1, Amita Jain2,

Zameerul Hasan1, Priyanka Gaur3, Sarika Panday1

1Department

of Respiratory Medicine, King George’s Medical University, India

2Department

of Microbiology, King George’s Medical University, India

3Department

of Physiology, King George’s Medical University, India

*Address

for Correspondence: Mr. Rajeev Kumar, PhD Scholar, Dept. of Respiratory

Medicine, King George’s Medical University, UP, Lucknow, India

ABSTRACT- Background: Multidrug-resistant

tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is caused by strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, it is

transmitted through air droplets from infected person and Close contacts of

MDR-TB patients have a high potential to developing TB. This study aims to

determine the profile of TB/multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) among household

contacts of MDR-TB patients.

Material

and Methods: The cases were recruited

from the King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India. In this

cross-sectional study, Close contacts of MDR-TB patients were screened for

tuberculosis. clinical, radiological and bacteriological experiments were

performed to find out the evidence of TB/MDR-TB.

Results: The

cases were enrolled Between December 2015 to December 2016, a total of 100

index MDR-TB patients were recruited which initiated on MDR-TB treatment. A

total of 428 contacts who could be studied, 11 (2.57%) were diagnosed with

MDR-TB and 4 (0.93%) had TB. The most frequent symptoms observed in patients

were cough, chest pain and fever.

Conclusions: Tracing

symptomatic contacts of MDR-TB cases could be a high yield strategy for early

detection and treatment of MDR-TB cases to contribute to reduced

morbidity, mortalityand to cut the chain

of transmission of infection in the community. The approach should be

bringing about for wider implementation and dissemination.

Keywords: TB,

MDR-TB, Symptomatic, Household, Transmission

INTRODUCTION-

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is caused by strain of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis that is resistant to at both isoniazid (INH,

H) and rifampicin (RMP, R) that are two

most powerful 1st line anti TB drugs, it is transmitted through

air droplets from infected person and Close contacts of MDR-TB patients have a

high potential to developing TB.

Because of the emergence of resistant

nature of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains, tuberculosis adopted more

alarming nature in the form of MDR-TB, is a global occurrence that poses a

serious threat to ongoing national TB control programmes. India accounts for about a quarter of the global TB

burden. Worldwide India is the country with the highest burden of both TB and MDR-TB [1]. There

are an estimated 79,000 multi-drug resistant TB patients among the notified

cases of pulmonary TB each year. According to WHO. In 2016 an

estimated 28 lakh cases occurred and

4.5 lakh people died due to TB.

According to the 2017 World Health Organization

global report, approximately 490000 people were infected by MDR-TB. In

addition, there were an estimated 110,000 people who had rifampicin resistant TB (RR-TB). So the number of

people estimated to have had MDR-TB or RR-TB in 2016 was 600,000 with approximately 240,000 deaths. Almost half (47%) of these cases were in

India, China and the Russian Federation, in which India has highest TB

incidence in Asia [1].

The prevalence of MDR-TB in India is

reported to be around 3% in new cases and 12-17% in retreatment cases [2].

Close contacts of MDR-TB cases are expected to be at increased risk of

developing TB due to intense and/or prolonged exposure to index cases in the

weeks to months before diagnosis and treatment beginning [3].

However, contradictory statistics have emerged from different existing studies

concerning the risk of TB in close contacts of drug-susceptible and MDR-TB

patients. A number of studies have reported a comparable risk of transmission

in the two groups [4–6], whereas others have not [7]..

Global TB Report 2017

released by the WHO, India, along with China and Russia, accounted for almost

of half of the 490,000 multi-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) cases registered in

2016, but limited data are available from India

to date on the occurrence of TB/MDR-TB among household contacts of MDR-TB

patients. Contact tracing in general is supposed to provide two functions: (1)

identifies contacts with TB disease so that treatment can be initiated early

when disease is more restricted- this in addition serves to decrease

transmission and (2) identifies high-risk infected contacts who might

assistance from either anticipatory treatment or close surveillance [8].

The objective of our study was to estimate

the incidence of TB in household contacts of MDR-TB patents registered at the

DR-TB center KGMU. Many risk factors that

are associated to development of MDR-TB have been reported among contacts but

have not been concurrently assessed. The present study was carried out to

determine the proportion of household contacts, whodevelop

active TB due to direct transmission from an index case in that household

through the clinical, radiological, and bacteriological profile in household

contacts of MDR-TB patients at a tertiary TB care center in Lucknow.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Setting and Study

design- A cross-sectional study was conducted at

the Department of Respiratory Medicine King George’s Medical University

DOTS-PLUS center, which covers 24 Districts of

Uttar Pradesh. The study population includes all the house hold contacts MDR-TB

patient registered under categary iv drug

regimen of DOTS-PLUS program at DR-TB centre were recruited from December 2015

to December 2016. A total of 100 MDR-TB cases were recruited for this study

after given inform consent. The study was ethically approved by institutional

ethics comitte. All index cases were retreatment

patients who had unsuccessful treatment with 1st line drug

regimen. The majority were residing in urban slum areas and were of poorer

socio-economic position. After an initial phase of hospitalization of about one

month, all index cases received supervised ambulatory treatment with

second-line drugs.

Screening contact

practice at the hospital- At the DOTS-PLUS center, it was a regular work practice to enquire all index

cases if any there family member had pulmonary symptoms (fever, weight loos,

cough and loss of appetite) suggestive of TB. If any symptomatic family members

were recognized, the index case was encouraged to take the family member for

further examination at the hospital.

The DOTS-PLUS center team

did thorough clinical examination of the symptomatic family member together

with detailed history, physical examination, and laboratory work up as per the

guideline of Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. Close contacts

with no active TB disease were monitored carefully for at least two years. It

is more important to careful and close follow-up was encouraged for infants and

children less than 5 years of age because they are more prone to suffer from the

disease. Household contacts with no suggestive signs and symptoms of active TB

were aware regarding the signs and symptoms of TB, about their contact with an

MDR-TB index case and about the significance of seeking treatment immediately

if they develop signs and symptoms of TB disease. Follow up monitoring was done

every 1–2 months. Contacts from Lucknow and nearby places, a team

composed of community health workers and medical officer conducted home visits

after every 1-2 month to trace. Those contacts, who came from

outside Lucknow were motivated to visit the DOTS-PLUS center KGMU after every 1–2 months to undergo the

study investigations.

Data collection- After

obtaining informed consent, a standardized case-report form was filled out for

all contacts of each index patient. Sex, age, weight clinical examination

assessment, radiological assessment, closeness to the index case, bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG)

scar (presence/absence to assess infection rates among vaccinated and

unvaccinated groups) and any history of TB (pulmonary/extra-pulmonary) were

also recorded.

Socioeconomic status based on education,

occupation and family income were classified by using modified Kuppuswamy scale [9].. Nutritional

status was assessed using the body mass index [10].. Sputum

examination for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on two early morning samples on 2

consecutive days was carried out in all contacts and in case of any positive

result for sputum microscopy, these cases were referred to Intermediate

Reference Laboratory (IRL) for Xpert MTB/Rif

resistance testing. On confirmation from IRL for Rifampicin resistance

on Xpert MTB, these patients were

registered at DOTS-PLUS to start cat 4 treatments. Those cases with no Rif

resistant to Xpert MTB although positive

for sputum microscopy were referred to respective DOTS centres for registration

and treatment initiation. Tuberculin skin testing (TST) using 5 tuberculin

units (TU) purified protein derivative (PPD) was performed in all contacts and

was recorded after 48-72 h at the study center.

A reading of ⩾10

mm was taken as positive. All contacts were also offered human immunodeficiency

virus and Diabetes testing.

Some of the Contacts that were not

available at the time of home visit for interview, their history were obtained

from the index cases or from other relatives of the family. In the case of

casualty of any contact members because of TB, a history was obtained from the

index patients or from other relatives of the family.

The ‘Index case’ was defined as the first

identified case of MDR-TB in the house. All index cases were confirmed by

sputum culture as having MDR-TB

A household Contact case was defined as

any person who shared the same enclosed living space for least 3 months prior

to the identification of the index case and included spouses, children,

parents, siblings and other family members (uncles, grandfathers, cousins).

RESULTS- Between

December 2015 and December 2016, 100 index patients were reviewed that

were started Anti-tuberculosis treatment. Their demographic profile is

shown in Table 1. Over a 67 (67%) were male and 33% female. 54% index

cases belong to urban and 46% belong to rural areas. Out of 100 index

cases Seven (7%) had previous and Nine (9%) had present

history of tuberculosis and majority of index cases were retreatment patients

that received treatment either of first line anti TB drugs of WHO treatment

category regimen previously. In the study population, 410 (80.7%) were HIV

negative, ninety eight (19.3%) of confirmed MDR-TB index cases were also HIV positive.

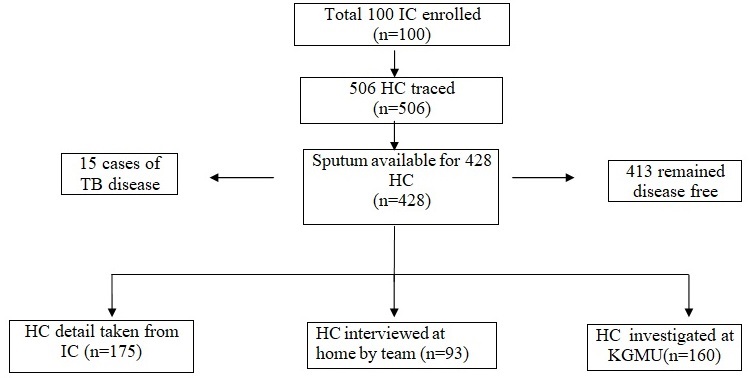

Fig. 1:

Flow diagram representing contact

tracing and outcomes of household contacts

(TB = Tuberculosis, IC= Index

cases, HC= Household contact, KGMU= King George’s Medical University, n= Number

of patients)

Table

1: Socio Demographic characteristics of Index case (IC)

|

Variables |

Frequency

(n=100) |

(%) |

|

Sex Male Female |

67 33 |

67 33 |

|

Age ≤

40 >40 |

58 42 |

58 42 |

|

Residence Urban Rural |

54 46 |

54 46 |

|

Personal

habit Alcoholic Non alcoholic Smoker Ex-smoker Non-smoker |

17 83 27 4 69 |

17 83 27 4 69 |

|

HIV

status Positive Negative |

22 88 |

22 88 |

|

Contact

history Present Past Absent |

7 9 84 |

7 9 84 |

|

Smear

Grading 3+ or 2+ 1+ or scanty |

54 46 |

54 46 |

|

Culture

Result Positive Negative |

98 2 |

98 2 |

The household contacts of the index cases

were identified using the medical records of the index cases that were present

in DR-TB center and through interviews of

index cases and their family members; symptomatic contacts or family members

recognized on the screening form and attached with the respective index case

file.

There were 506 household contacts of 100

index patients were screened for tuberculosis. Their demographic profile is

shown in Table 2. Majority of contacts (67.6%) were male and most of them

(70.4%) belong to the urban area.

Table

2: Socio Demographic characteristics of household contact (HC)

|

Variables |

Frequency

(n=506) |

(%) |

|

|

Sex Male Female |

342 164 |

67.6 32.4 |

|

|

Age ≤

40 >40 |

318 188 |

62.8 37.2 |

|

|

Residence Urban Rural |

356 150 |

70.4 29.6 |

|

|

Personal

habit Alcoholic Non

alcoholic Smoker Ex-smoker Non-smoker |

54 401 94 37 375 |

10.7 89.3 18.5 7.31 74.1 |

|

|

Smear

Grading 3+

or 2+ 1+

or scanty |

(n=15) 11 4 |

73.3 26.7 |

|

|

Culture

Result Positive Negative |

(n=428) 15 413 |

3.50 96.5 |

|

|

Drug

susceptibility testing Resistance Susceptible |

11 4 |

73.3 26.7 |

|

|

Number of

contacts who developed MDR-TB per

household One Two Three |

11 3 1 |

73.3 20 6.7 |

|

Three hundred eighteen (62.8%) of the

contacts have ages bellow to 40 years that are the most susceptible age group

of the population. A symptomatic household contact was identified in 15 of 428

(3.50%) index cases. The most common symptoms were a cough followed by fever

loss of appetite and haemoptysis. History of loss of weight was also present in

all 15 contacts. Sputum specimens were collected and examination was performed

for 428 (83.99%) household contacts, whereas the remaining 78 (15.4%) were

unable to provide sputum for examination. Chest X-ray was performed in 228

contacts. Sputum for AFB yielded negative result for 413 (96.4%) cases while it

was positive in 15 (3.50%), sputum smear positive cases had smear

grading 3+ or 2+ for 11and 1+ or scanty for 4.

All

sputum positive and other suspected cases were referred to Intermediate

Reference Laboratory (IRL) for Xpert testing

and Drug susceptibility testing (DST). Xpert and

DST results of 11 (73.3%) contacts confirmed MDR-TB while 4 (26.7%) was

declared drug-susceptible TB. Four contacts that were diagnosed with pulmonary

TB were referred back to their respective district for registration at

DOTS center for category first whereas the

remaining 11 contacts that were diagnosed as MDR-TB patients were registered

for drug resistant TB treatment at DR-TB center KGMU.

DISCUSSION- In

India, the main objective of National DOTS-Plus Programme is to reduce

tuberculosis transmission by providing early diagnosis and treatment of MDR-TB

patients, for that, it follows the entire protocol of MDR-TB to facilitate

prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and to cover the entire nation with the

scheduling and monitoring in a phased manner. Household

contacts constitute a high-burden group for developing TB and MDR-TB, and the

significance of selective case detection in these groups cannot be

overemphasized. Recently infected contacts carry an eightfold risk of

developing TB compared with persons infected more remotely [11]. While

not all cases found through household contact tracing are the result of

transmission from the index case, early detection and treatment of the

contagious cases will greatly reduce the transmission rate in the

population [12,13]. Because of frequent exposure to index

patient, household contacts of MDR-TB have more recurrent threat to developing

active TB and MDR-TB. On the other hand, available information on subsequent

risk of developing active TB/MDR-TB disease among MDR-TB

contacts have not been reliable. There are very few studies reported

from India on the burden of disease and infection among contacts of MDR-TB

patients. Singla et al reported that TB

prevalence among contacts was 5.3%, of whom only 0.7% had MDR-TB [2]

In

the present study, we measured the factors that are related to contacts such as

residence, any history of TB treatment, HIV status, sex, age, and number of

confirmed MDR-TB in the house. In this study, a total 428 contacts of index

patient studied, of which, 11(2.57%) contacts developed MDR-TB while 4(0.93%)

cases developed drug susceptible TB subsequent to the index case. The Overall

rate of disease in the present study was 3.50 % which is very low as compared

to an earlier study conducted by Dhingra et

al. [14] who reported a 53.5% prevalence of TB

infection in household contacts. We could not determine that household contact

gets infected by transmission from index case as we were not performed genetic

study of mycobacterium. However, as we know it is a communicable disease, there

is significant proof to support the transmission of MDR-TB strain from person-to-person

in the community. It was shown by Bayona et

al. [15] that over half figure of global MDR-TB cases

are thought to result from primary transmission. In addition, the transmission

may have taken place previously, when they were drug-susceptible, as most of

the index cases were retreatment cases. This study had a number of functioning

problems with the simple contact tracing and testing strategies used. Almost a

third of close contacts with cough for more than two weeks

could not provide sputum samples for smear microscopy. While a

number of contacts were unable to produce sputum sample when needed, many

others were simply not present at their home at the time

of visiting the team of DR-TB center.

There are a number of limitations in our study. First, the small sample size of

drug-resistant contact cases due to the inability to trace all the contacts.

Second, data on several determinants for the MDR-TB disease were absent from

analysis because they were not in the routine registers patients. Third, we

considered only household contacts that are living with index patient and not

other casual or close contacts.

CONCLUSIONS- Present

study highlights the requirement for early detection and treatment of TB in

household contacts of MDR-TB, who represent a high-burden group, and also

suggest that active tracing of symptomatic contacts; cases contribute

to reduced morbidity, mortality and transmission of infection in the society.

This could be a very effective approach to saving more people as well as in cutting

the chain of the transmission in the community. The conclusions from this

study are believed to notify the national MDR-TB treatment carrying out plan as

well as other similar countries in their attempt to roll out MDR-TB treatment

services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS- We were greatly thankful to Uttar Pradesh Council of Science and Technology (UP-CST), Lucknow for provided funding and department of Respiratory Medicine, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India and also appreciates patients participated in this study.

REFERENCES

1.

WHO Global TB Report, 2017.

2.

Singla N, Singla R,

Jain G, Habib L, Behera D.

Tuberculosis among household contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

patients in Delhi, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2011;

15(10):1326–1330.

3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious

tuberculosis, 2005; 34:1–37.

4.

Teixeira L, Perkins MD, Johnson JL, et al.

Infection and disease among household contacts of patients with multidrugresistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2001; 5: 321–328.

5.

Schaaf HS, Vermeulen HA, Gie RP, Beyers N,

Donald PR. Evaluation of young children in household contact with adult

multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis cases. Pediatr Infect DisJ, 1999; 18: 494–500.

6.

Schaaf HS, Van Rie A, Gie RP, et al. Transmission of multi drug resistant

tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J,

2000; 19: 695–699.

7.

Siminel M, Bungerzianu G, Anastasaty C. The risk of infection and diseases in

contacts with patients excreting Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensitive

and resistant to isoniazid. Bull IntUnion Tuberc, 1979; 54:

263.

8.

Mulder C, Klinkenberg E, Manissero D. Effectiveness of tuberculosis contact

tracing among migrants and the foreign-born population. Euro Surveill Rev Artic,

2009; 14(11):11.

9.

Kuppuswami B. Manual of socio-economic scale

(urban). New Delhi, India: Manasayan, 1981.

10.

Kuczmarski RJ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM, Troiano RP.

Varying body mass index cut-off points to describe overweight prevalence among

US adults: NHANES III (1988 to 1994). Obes Res

Nov, 1997; 5: 542–548.

11.

American Thoracic Society and Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention. Targeted tuberculin and treatment of

latent tuberculous infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med,

2000; 161 (4 Pt 2): S221–S247.

12.

Long R, Schwartzman K. Pathogenesis and transmission of tuberculosis.

In: Canadian tuberculosis standards. Vancouver: Canadian Thoracic Society

Canadian Lung Association Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014.

13.

Devadatta S, Dawson JJ, Fox W, et al. Attack

rate of tuberculosis in a 5-year period among close family contacts of

tuberculosis patients under domiciliary treatment with isoniazid plus

PAS or isoniazid alone. Bull World Health

Organ, 1970; 42: 337–351.

14.

Dhingra VK, Rajpal S, Aggarwal N, Taneja DK.

Tuberculosis trend among household contacts of TB patients. Indian J Community

Med, 2004; 29: 44-48.

15.

Bayona J, Chavez-Pachas AM,

Palacios E, Llaro K, Sapag R, Becerra MC. Contact investigations as a means

of detection and timely treatment of persons with infectious

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2003;

7(Suppl 3): S501-S509.